I once dated a chef who had a gigantic portrait of Anthony Bourdain above his kitchen. In contrast, it reminded me of the sign above my kitchen sink in my childhood home that read ‘Slave Quarters.’ Yikes! I know. Lately I’ve been seeing blogs revisit the question that’s followed Bourdain’s death since it was made public:

How could a man so well-traveled, so full of life, take his own?

I don’t have the answer. I just have the experience.

But first, back to these kitchens.

The hospitality industry was my way of going to the military without ever really signing my life away. The structure, discipline, quick thinking, procedures, and remaining calm under pressure, it’s essential to a shift. Required, even. Suppressing your emotions, ignoring physical pain, shelving any part of yourself that isn’t “on” so that everyone else gets their food, their experience, their moment — that’s the expectation. It’s war, but the weapons are ramekins and piping hot plates, and the battlefield is a dining room full of people who believe they’re the only ones that matter.

There’s a reason so many people with trauma or depression end up in restaurants. The urgency feels familiar. The chaos makes sense. There’s comfort in the constant motion because slowing down forces you to feel. And when you’re good at it, when you can juggle eight tables while bleeding through your shoes or biting down a panic attack between courses, people call you strong. They tip you for surviving. And then they leave.

I didn’t need boot camp. I already knew how to dissociate and keep working. The kitchen just gave it a name. Gave it a uniform. Gave it a hierarchy that mirrored the ones I grew up under. You earn your respect by shutting the fuck up and showing up. And when you finally break down — because everyone eventually does — it’s back to the walk-in fridge, alone, so you can scream into a side of salmon and wipe your face with a bar rag before table 42 asks about the specials.

Hospitality taught me precision, grace, resilience, but also how to hide. How to pour myself into the needs of strangers because mine felt too complicated. It’s an industry built on performance, on suppressing your humanity for a polished guest experience. And when you already grew up doing that just to survive a household, it doesn’t feel like a job. It feels like home.

Whether you’re front or back of house, in a restaurant you have to be attuned to the absurdities, contradictions, and social pressures it takes to run, especially if it’s a damn good one. This is a stage. Are you showing up with or without your mask on?

The chef I dated had accolades. His own restaurant. Magazine spreads. Mentions alongside Bobby Flay and Guy Fieri. But when he spoke about any of it, there was a flatness in his tone like he had completed the assignment and now just… existed inside the result. Not depressed exactly. Not proud either. Just… there.

That portrait wasn’t just homage — it was kinship. And I was picking up what he was putting down.

Because even after I escaped my abusers. Even after starting my own business. Even after people started paying me for my words. Even now — I don’t feel excited. I never really have. Not in a way that lasts. My brain processes the good the same way it does the bad: like data. Like something to hold and survive. And when survival is the setting, joy never really lands.

Existential fatigue doesn’t always look like tears or broken glass. Sometimes it looks like a Michelin star, a book deal, a paid invoice — and a face that never lights up genuinely when talking about it.

Remember how I said you have to be attuned to the absurdities when working in a restaurant. Imagine that while literally traveling and exploring the absurdities of life.

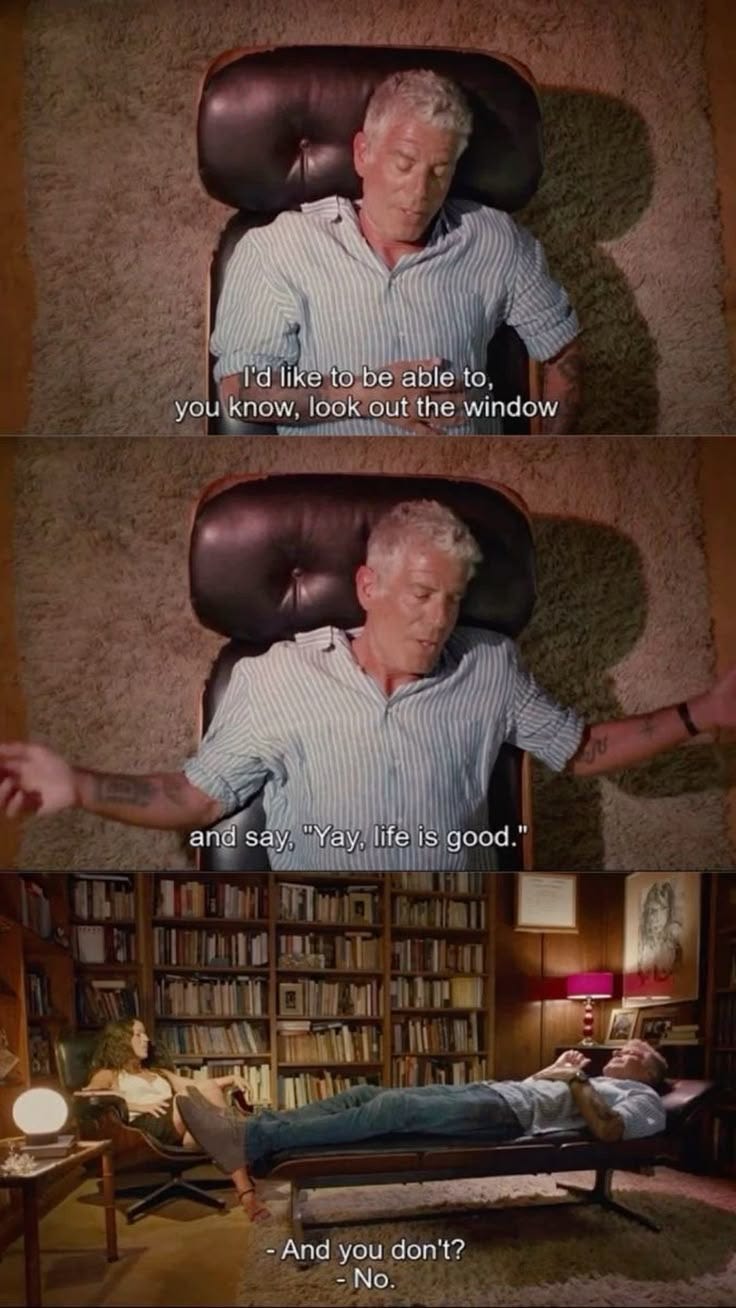

Anthony Bourdain’s articulation of how absurd life can feel was appealing because he delivered it with charisma, wit, and a sense of detached cool that mirrored the emotional state many people were silently living in. He didn’t shy away from discomfort or contradiction. He spoke in circles that sounded like clarity. He wrapped weariness in curiosity and gave disillusionment a passport.

What people were drawn to was not just his hunger for culture, but the way he named the emptiness that sometimes followed fulfillment. He could be standing in front of the most beautiful plate of food in the most remote corner of the world, and still, you could feel it — that flatness in his tone, the slight delay in his smile, the soft edge of melancholy tucked behind the punchlines.

He made existential fatigue look manageable. Digestible. Even seductive. Because he kept going. He worked, he wandered, he reflected. And that’s what confused people. We’re conditioned to believe that motion equals meaning. That success means wellness. That access to beauty and wonder is enough to sustain you.

Albert Camus once asked, “Should I kill myself, or have another cup of coffee?” The “coffee” becomes the small act of resistance: finding tiny, tangible reasons to keep going even when nothing feels coherent.

You don’t think food became a small act of resistance for Bourdain?

If you still can’t fathom why he took his own life, then maybe you’re not ready to accept that suicide is sometimes a confession — not always of weakness, but of truth. A final admission that life was either too much to carry or too senseless to keep trying to understand.

I know this feeling. I’m living this feeling. i keep getting called back to meditation. It’s the one thing that makes me feel like “yes it’s all happening, everything matters, nothing matters, and it’s truly okay” and when I’m in that space it feels like fulfillment is really just acceptance

I've been watching Parts Unknown, slowly drawing it out so I don't have to bawl my eyes out just yet, for the last few months while unemployed and yeah his mental state gets more & more apparent as it goes on.

I was really struggling a few months ago and kept thinking of him and Robin Williams, but a mix of meditation, weed & music brought me back into alignment. Anyone that reads this, I hope you find your greener side wherever that is ❤️